Leg 4, Blog 11, January 12, 2026

We left the Melchior Islands mid morning on January 3rd on our way to Waterboat Point (next blog). On our way to Waterboat we passed by incredible glaciers, icebergs and ice-filled passages.

One of the smaller glaciers that we passed.

Above: Lone penguins atop a snow mass just hanging out.

Above: It was not uncommon to see these massive icebergs (they floated in from a calving glacier) as part of the landscape.

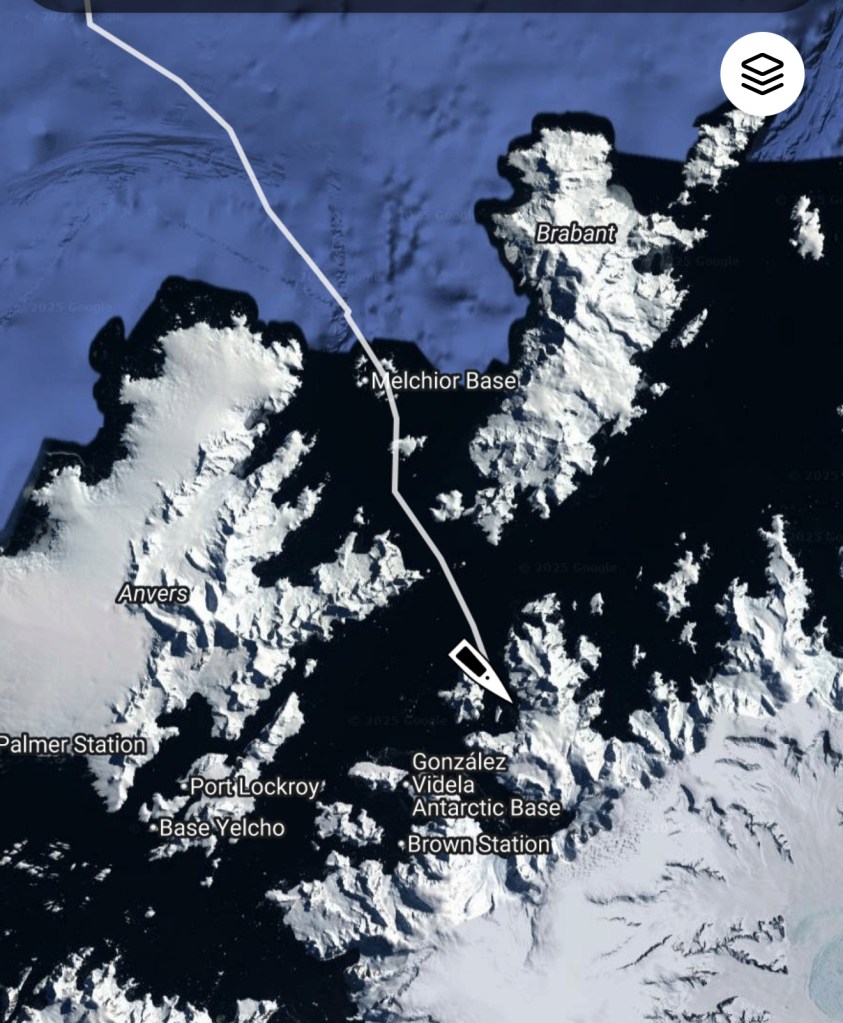

CUVERVILLE ISLAND

Cuverville Island is a small, rocky island on the northern end north of Rongé Island which we would pass on our way to Waterboat. Cuverville, which is a destination onto itself, was discovered by Adrien de Gerlache who led the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899. He named the island after Jules de Cuverville, a French naval officer who became the Chief of Staff of the French Navy in 1898.

This was the first purely scientific expedition to Antarctica. It was also the first time that an expedition wintered in proper Antarctica. Moreover, Roald Amundsen was a part of the expedition team, so it was fun and historic to follow in his footsteps.

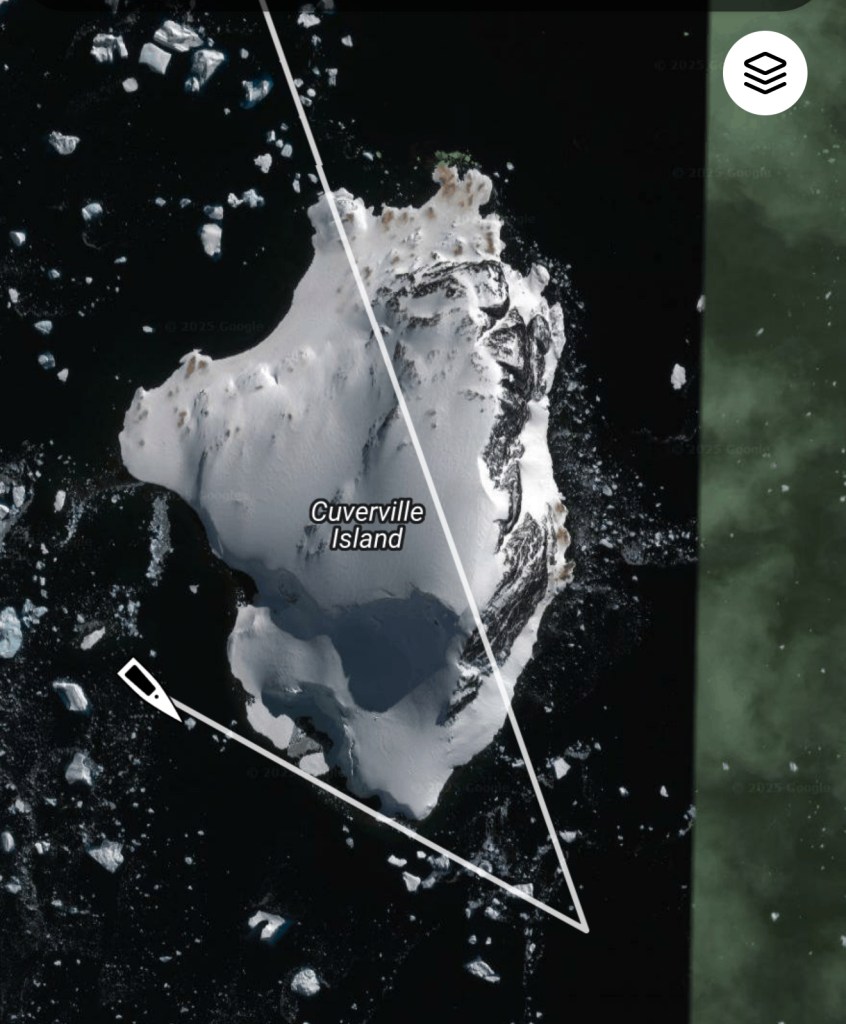

Above: As we approached Cuverville, the water filled with small bits of ice that were remnants of calving glaciers or icebergs. If you can remember back to our Arctic days, a “burgy bit” is generally defined as having a height of more than 3 feet but less than 16 feet above sea level, and a length typically around 15 to 45 feet. This places them between “growlers” (smaller, about the size of a grand piano) and full “icebergs” (larger than 15 feet above sea level).

This small ice was not a problem to pass through as this is what Mōli, with her thick aluminum hull, was designed to push through. The problem, of course, is that we had to go slow to avoid contact with the bigger bits that hid themselves. Few sounds in life are as upsetting and disconcerting as that telltale “THUNK” when your hull comes into contact with a large enough piece of ice to cause a scratch or dent in even a thick hulled boat. And a fiberglass hull, well, “Fuhgeddaboudit!”

Above: As we approached the island, the massive penguin colony came into view. The prime attraction of Cuverville Island is the extensive gentoo penguin colony. As per estimates, more than 4,500 penguin pairs are living on the beach and the coves on the northern parts of the island. This is reported to be the largest population of gentoo penguins in the Antarctic peninsula.

Above: We passed by a cruise ship that was anchored about one mile up the passage. They were out exploring the nearby glacier, doing some ice scuba diving and viewing a couple of areas of the gentoo colony (there were many). I was chomping at the bit to get off the boat and into my first Antarctic penguin colony. Randall looked at me with despair as he announced that wind conditions would not allow us to set anchor in a safe and secure manner. We would just have to pass this colony by and explore the next one at Waterboat Point.

I did not say anything, but the look of despair on my face must have moved Randall. “OK”, he said, “We call pull into this cove ahead, drop anchor, and you can take the dingy and go to the colony to explore while I wait here on the boat”. “YES THANK YOU!!”

Above: It was a short dingy ride into this remote cove of the island. I came immediately into contact with thousands of penguins. What about the above group? Was this a colony or a rookery?

I did some quick research and a colony is a general term for any large, social gathering of penguins on land. Penguins are highly social birds, and they congregate in these large groups for safety and social interaction throughout the year.

A rookery is a more specific term for a breeding colony. This is the location where all nesting, egg-laying, and chick-rearing activities take place. (So look at the picture above and notice the penguins lying in their nest, protecting their eggs or hatchlings. The term breeding colony emphasizes the reproductive purpose of the gathering. The sheer number of birds in a rookery can be massive, sometimes reaching up to a million nesting pairs (not penguins, of course).

So it safe to say that Cuverville was both a rookery and a colony. As you can see from the pictures in this blog, I saw virtually no hatchlings in this rookery. Every breeding colony in the Antarctic has its own pace and timing. This was a fairly latent group, meaning that they are late breeders and only had eggs at this point, almost no cute little hatchlings yet.

Above: It’s hard to tell the boys from the girls, but you can see a couple of penguins in their off time. No need for them, at the moment, to be in the nest to hold the eggs. They just walk around looking to grab a rock or two for their nest which seems to upset the other penguins.

Above: While it might look like they’re just daydreaming and posing for photographs, for penguins, standing still is actually a high-stakes survival strategy.

- Conserving Energy: Moving on land is exhausting for penguins because their short legs and heavy bodies are designed for “flying” underwater. Standing still allows them to save their precious fat reserves for staying warm or traveling back to the ocean to hunt.

- Sleeping on the Go: Penguins often take thousands of “micro-naps” throughout the day that last only seconds. Standing up lets them nap while staying alert for predators or protecting an egg on their feet.

Above: My wife Jorun pointed out to me that the most remarkable feature of penguin feet is their ability to avoid freezing in sub-zero temperatures, largely due to a system called countercurrent heat exchange.

- Countercurrent Heat Exchange: Warm arterial blood flowing from the penguin’s core to its feet passes close to the cold venous blood returning from the feet. Heat is transferred from the warm blood to the cold blood, meaning the blood that reaches the feet is already cool (just above freezing), minimizing heat loss to the environment. The returning blood is pre-warmed before it reaches the core, which conserves body heat.

- Blood Flow Control: Penguins can control the amount of blood flowing to their feet by constricting or dilating blood vessels, further regulating heat loss.

- Behavioral Adjustments: Penguins employ specific behaviors to manage temperature, such as huddling together for warmth, or rocking back onto their heels to reduce contact with the ice. When they get too warm, they can also increase blood flow to their unfeathered feet to dissipate excess heat.

Above: There is so much going on in a penguin colony at any given moment. I find this very reminiscent of life in the shtetl (Yiddish for “little town” or small, predominantly Jewish town or village in Eastern Europe before WWII). There is nothing “Jewish” about a penguin, but their tight-knit, self-sufficient community centered on family, tradition, with their own language and with life revolving around nesting, feeding and gathering rocks reminds me of life in the “old country”.

Above: No obligation whatsoever, but if anyone has an idea of the meaning and purpose of the encounter between the two penguins above, please let me know!

Above: To me, this picture is evocative of a high Himalayan town or village that is nestled in the world’s tallest mountain range, known for stunning scenery, unique cultures,and extreme altitudes. Can the Dalai Lama be far away?

Above: Here is a similar picture to the one above illustrating the stunning, beautiful locations of their habitat.

Above: This video starts off with a jaunting gentoo, and finishes with a shot of a parent feeding one of the few hatchlings in the rookery.

Above: Time for a swim and perhaps some feeding….

Above: With Randall still on the boat, it was time to leave Cuverville Island and say goodby to all of my gentoo friends.

Nothing like returning to the mother ship after a life changing afternoon with this gentoo colony.

Leave a comment